The relevant term “electricity producer” in the context of CO2 emissions trading

A few days before the end of the application period for free allocation for the fourth European emissions trading period, the bombshell burst. In its judgment on the ExxonMobil action, the ECJ defined the term “electricity producer” very narrowly. Plant operators who operate a power plant for the production of electricity and heat are likely to be classified by DEHSt as “electricity producers“, even if the purpose of the power plant or CHP is to provide heat and electricity for industrial production.

The consequence for many plant operators who do not operate a so-called “high-efficiency CHP plant” is probably that a free allocation for the heat produced can only be achieved for the district heating share.

Electricity generators according to EU Emissions Trading Directive

The current version of the EU Emissions Trading Directive states:

“electricity generator” means an installation which generated electricity for sale to third parties on or after 1 January 2005 and which does not carry out any activity listed in Annex I other than the “combustion of fuels”.

Even if only a single kWh of the electricity generated has been used outside the boundary of the installation subject to emissions trading since 2005, the installation operator may be classified as an electricity producer, which, in simple terms, has two adverse consequences for the quantity of free allocation of emission allowances.

First, “electricity generators” will face a further reduction for free allocation compared to non-generators under Article 23 of the EU Allocation Regulation with the linear reduction factor.

Secondly, and much more relevantly, the entire free allocation for the heat produced by industrial companies operating power plants may now be at stake as a result of the ECJ ruling.

The German Emissions Trading Authority (DEHSt) has not yet been able to reflect the consequences resulting from the ruling on the ExxonMobil lawsuit in the guidelines for the 2021-2030 allocation procedure; accordingly, it is difficult for plant operators to estimate the consequences resulting from the classification as “electricity producers”.

Reason enough to have this ECJ ruling described by an expert. GALLEHR+PARTNER® has asked our long-standing network partner and emissions trading expert, lawyer and specialist in administrative law, partner of Köchling & Krahnefeld Rechtsanwälte Dr. Markus Ehrmann, to explain this ruling in a guest article for non-lawyers:

ECJ Judgment of 20 June 2019 in the “ExxonMobil” case – summary and assessment.

Guest commentary: Lawyer Dr. Markus Ehrmann Köchling & Krahnefeld Rechtsanwälte Partnerschaft mbB

In its June 20, 2019 ruling in ExxonMobil (Az. C-682/17), the ECJ gave rulings on three aspects:

First, the ECJ addresses the scope of application of the European Union Emissions Trading Scheme (EU ETS) and interprets it broadly (for more on this see 1.). The ECJ then had to deal with the definition of the term “electricity producer” and interpreted it just as broadly (on this under 2.). Finally, the ECJ answered in the negative the question of whether heat produced in a plant for electricity generation but not used for electricity generation can be allocated free of charge (on this subject see 3.).

In detail

I. Judgment of the ECJ

The ruling was based on the following technically complex plant constellation: The company ExxonMobil Produktion GmbH (hereinafter: ExxonMobil) operated a plant in which a product (sulphur) is extracted in the course of natural gas processing by means of an activity not subject to emissions trading.

At the same time, the installation generates electricity and heat through an activity subject to emissions trading (combustion of fossil fuels in an installation with a rated thermal input above the relevant threshold of 20 MW). In turn, the electricity is mainly generated for the plant’s own needs and only a small proportion is fed into the public grid for a fee.

1. scope of application of the EU ETS

Before dealing with the actual questions as to whether this plant constitutes an electricity generator, the ECJ first dealt with the question of whether the plant is subject to the EU ETS at all, almost as a preliminary question.

The EU ETS Directive applies to the “activities” listed in Annex I to this Directive if they result in emissions of greenhouse gases. Here, ExxonMobil had pointed out that the greenhouse gas released was so-called “inherent CO2“, i.e. CO2 that was naturally present in the raw material used.

However, according to the ECJ’s decision, this does not preclude the application of the EU ETS. It does not follow from the wording of the EU ETS Directive that the greenhouse gas released must itself be produced by those activities. It is therefore irrelevant whether or not the CO2 resulting from the activity of that plant occurs naturally in the raw material processed there.

The ECJ therefore does not follow an original proposal by the Commission to distinguish between indirect and direct emissions.

Rather, if an activity subject to emissions trading is carried out in the installation through the combustion of fossil fuels, all emissions from the installation are subject to the EU ETS, even if they originate from an activity that is not itself subject to emissions trading, in this case sulphur extraction.

2. term power generator

The ECJ then had to interpret the term “electricity producer”. This interpretation gains in importance because electricity producers do not receive free allocation of emission allowances but have to buy them at auction.

The EU ETS Directive defines “electricity generator” as a facility that produces “electricity for sale to third parties”.

In the case at hand, it could be doubted whether the plant produces “electricity for sale to third parties”, since the electricity produced is mainly used for own consumption and only a small part is fed into the public grid against payment.

However, the ECJ notes that the wording of the definition of “electricity producer” does not contain any restrictive quantitative criteria or even a threshold for the sale of electricity to third parties. So this does not have to be done exclusively or primarily.

Accordingly, the concept of electricity producer must be interpreted broadly in the present Decision. Any sale of the electricity generated to third parties, i.e. any feed-in, however small, of the electricity generated into the public grid, results in the installation in question being regarded as an electricity generator. This further restricts the possibility of allocating emission allowances free of charge.

3. allocation for heat

Insofar as the ECJ understands the term “electricity producer”, it also takes a narrow view of the exceptions to free allocation for heat production in electricity-generating installations. Until now, the principle has been that no free allocation is made for the production of heat for the purpose of electricity generation.

According to the decision of the ECJ, there is now also no free allocation of emission allowances for heat if this heat is consumed in an electricity-generating plant precisely not for the purpose of electricity generation. In addition to heat production for district heating, only heat from high-efficiency cogeneration is eligible for allocation in the case of plants classified as “electricity producers”.

The ECJ reaches this conclusion by interpreting the relevant provision on allocation for heat in the EU’s uniform allocation rules in the light of the EU ETS Directive. However, under the EU ETS Directive, the principle is that no free allocation can be made to electricity generators, with the sole exception that emission allowances are allocated free of charge for district heating and high-efficiency cogeneration in relation to heat production.

II. outlook

Overall, the ECJ decision paints a negative picture for operators of electricity-generating plants, so that it is necessary to ask how plant operators can avoid negative effects:

First, the scope of emissions trading is broadly understood. This means that emissions which do not themselves originate from an activity subject to emissions trading, if they occur in an installation subject to emissions trading, must also be reported and emissions allowances surrendered for them. In order to avoid this effect, the operators concerned could in future seek to split the installation concerned into two installations, where this is technically and legally possible. In the present constellation, this could mean, for example, splitting the plant into a sulphur production plant and a power plant.

Next, the ECJ interprets the term “electricity producer” broadly: Even if only a small amount of electricity is fed into the grid, free allocation is to be denied.

Finally, according to the ECJ ruling, no free allocation is to be made for the production of heat in an electricity-generating plant, even if it is not produced for the purpose of electricity generation, as long as this is not done for district heating and in a highly efficient combined heat and power plant. Heat generation in a non-high-efficiency industrial power plant would thus not receive a free allocation. It remains to be seen to what extent this ruling will affect the allocation of emission allowances for the fourth trading period currently pending a decision.

Finally, as the ECJ specifically emphasises that it does not impose any time limit on the effect of the judgment, there could be effects not only for the future, but existing allocations since 2013 could also be corrected retroactively.

-end of guest post-

Economic impact

If plant operators have so far been able to deal relatively calmly with the classification as “electricity producers”, the situation will change at the latest after the ECJ ruling. For the third emissions trading period, which has been running since 2013, it has been possible to realise a higher free allocation partly as a result of this classification. For the fourth emissions trading period starting in 2021, many things may now change after the ECJ ruling. Then, at the latest, there is a risk for quite a few of these plant operators that the entire allocation for heat production will be lost.

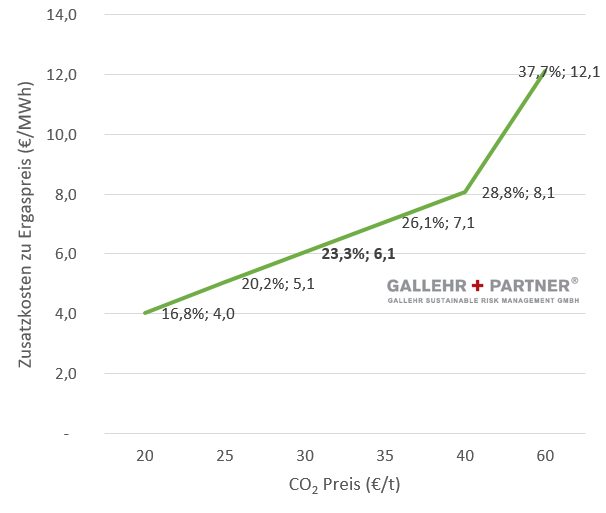

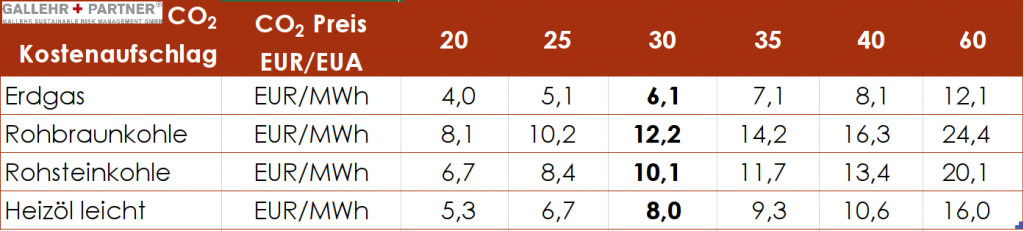

At a CO2 price of approx. 30€ per ton – the EUA price level is currently between 25 and 30 €/EUA – according to calculations by GALLEHR+PARTNER®, the CO2 costs of a natural gas-fired power plant are a substantial additional 6€/MWh of natural gas. At a wholesale price of €20/MWh natural gas, these six euros account for around 23% of the total costs.

For other fuels, the cost premium is even higher, as can be seen in the following table.

For other fuels, the cost premium is even higher, as can be seen in the following table.

With a natural gas consumption of 100 GWh/a and a CO2 price of 30€/EUA, about 600,000 €/a have to be priced in addition to the natural gas price in the full cost calculation today.

With a natural gas consumption of 100 GWh/a and a CO2 price of 30€/EUA, about 600,000 €/a have to be priced in addition to the natural gas price in the full cost calculation today.

Even if only 30% of the emissions released by natural gas combustion were covered by free allocation, the abolition of free allocation for a natural gas consumption of 100 GWh/a and a CO2 price of 30€/EUA would price in just under 200,000 €/a.

On the other hand, the continuing high CO2 price, according to the experts, can also be seen as an opportunity, especially in view of the currently very lucrative funding opportunities in the EU and at federal and state level. Now is the right time to invest in the future competitiveness of companies.

Assuming a total efficiency of the power plant of 90% and a CO2 price of 30€/EUA, an increase in efficiency of the company of a good 20% by 2021 would be sufficient to compensate for the additional burden of the CO2 prices. Irrespective of a classification as a “power generator”, GALLEHR+PARTNER® recommends that every industrial company, for purely economic reasons, should now at least develop a catalogue of measures to increase efficiency and compare this with the existing subsidy programmes.

Please do not hesitate to contact us if you have any questions regarding the professional evaluation of measures, the research of subsidies or the support during the implementation of measures and the management of subsidies.

Recommendations

In the last few days, some plant operators supported by GALLEHR+PARTNER® have received follow-up requests from the DEHSt via the Virtual Post Office (VPS) regarding the classification of the plant subject to emissions trading as an “electricity generator” with a very short response period of two weeks. These must be answered on time, independently verified and each electronically signed via the VPS. Please do not hesitate to contact us at any time.

However, GALLEHR+PARTNER® generally recommends that competent legal advice be sought in this case in order to formulate the answer. If you have general questions about the subsequent claim, it may be useful to make an informal telephone call to the DEHSt customer service.

Irrespective of the enquiries made by DEHSt with regard to the application for the free allocation of emission allowances for the fourth trading period, every plant operator who generates electricity in a plant subject to emissions trading and who does not carry out any other activities in this plant in accordance with Annex 1 TEHG as the “combustion of fuels”, deal with this circumstance of classification as an “electricity producer”. Whether and which measures are feasible to secure the free allocation of emission allowances for the 4th trading period must, however, be examined on a case-by-case basis.

So far GALLEHR+PARTNER® is not aware of any adaptation of the existing regulations by the DEHSt. In any case, the plant operators concerned must examine to what extent and under what conditions the replacement of the existing power plant by a high-efficiency CHP plant can lead to a reassessment of the free allocation for the fourth emissions trading period.

Here you can download this article as pdf.